Moas

Name: Moas (Dinornithiformes)

Conservation Status: Extinct

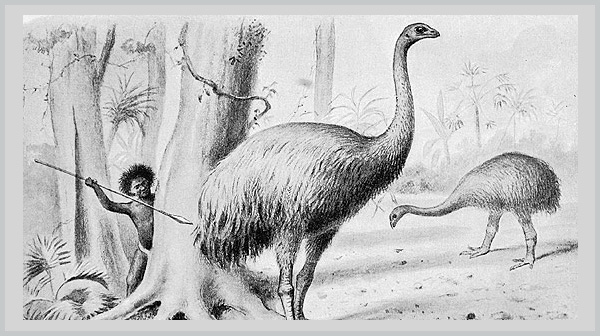

A mere 1,000 years ago, giant flightless birds called moas inhabited the islands of New Zealand. There were more than a dozen species of moa and the largest of these may have weighed more than 200 kilograms and stood 2 to 3 meters high. The different species of probably became extinct at different times, although little is actually known about this because the archaeological record is limited.

Like the Dodo in Mauritius, moas developed on isolated islands with limited contact with mammals and other terrestrial (land dwelling) vertebrates. Human beings did not colonize New Zealand until about 1,000 years ago when the first Polynesians arrived.

These new arrivals hunted these birds and it seems unlikely that any of the species survived into the time of the first contact with Europeans, in 1770.

Although the Maori, the native people of New Zealand, had oral accounts of these birds, Europeans did not learn of them until the 1830’s when scientists first analyzed some bone fragments and realized that giant birds had lived on the islands.

News of the moa’s existence caused great excitement among scientists and the general public who hoped that some could be found alive, although none ever were. They lived on only in traditional Maori accounts and Maori place names, such as Te Kaki o te moa (the neck of the moa) and Pukumoa (moa’s belly).

While it is possible that moa populations were already in decline due to natural causes when the first people arrived in New Zealand, the most likely explanation for their extinction is overexploitation by humans. There are numerous archaeological sites containing evidence of moa hunting by humans.

Since there were no other animals of comparable size to be found on the islands, moas most likely were the preferred prey of humans.

Other anthropogenic factors also may have contributed to the moas’ demise. These include predation of young chicks by dogs and rats that came to the islands with the first humans, and habitat alteration through extensive burning.

The Maori practiced burning because it tipped the balance of the ecosystem in favor of certain desirable plants and fish. Whatever the combination of factors, it is clear that the cause of moa extinction was the colonization of New Zealand by humans.

There have been quite a few reports of moa sightings over the years, especially in the earlier years of European colonization. Some scholars believe these indicate a post-colonial date of extinction.

The greatest period of sightings was from 1850 to 1880, after moas had received significant scientific and popular attention; not one of the sightings occurred prior to the original publication of information about moas. These factors make it unlikely that any of the sightings were authentic. There is no reasonable evidence to suggest that they survived into the 1800s.

Questions for Thought:

What is your reaction to the information about moa sightings? Does it make you skeptical of sightings of other possibly extinct species? Compare the moa sightings to sightings of other species such as the Tasmanian tiger-wolf, the Caribbean Monk seal, and the hairy-eared dwarf lemur.

The dodo and the moa have much in common. Both were large, flightless birds found on isolated islands. They developed apart from humans and most other terrestrial mammals, and both became extinct in roughly the same era because of hunting and other pressures caused by humans.

Yet, because the Maori had no written language, the story of the moas is known almost exclusively from archaeological evidence, while the dodo’s tale is known from written historical accounts. How might these different sources of knowledge affect scientists’ ability to describe what happened to these species?

Related Classroom Activities:

[CS2-8,C3-1,C3-2, General]